|

| ||

|

|

Statistically I should be dead or dying. Instead, I’m busy, in my 92nd year with another career.

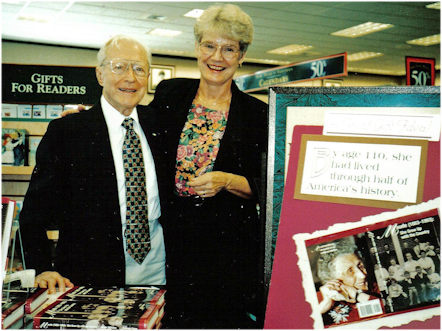

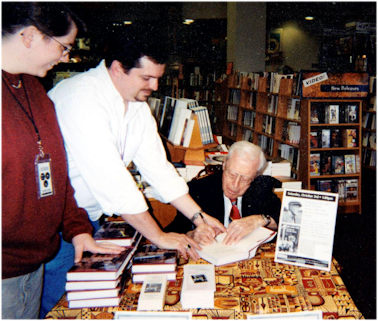

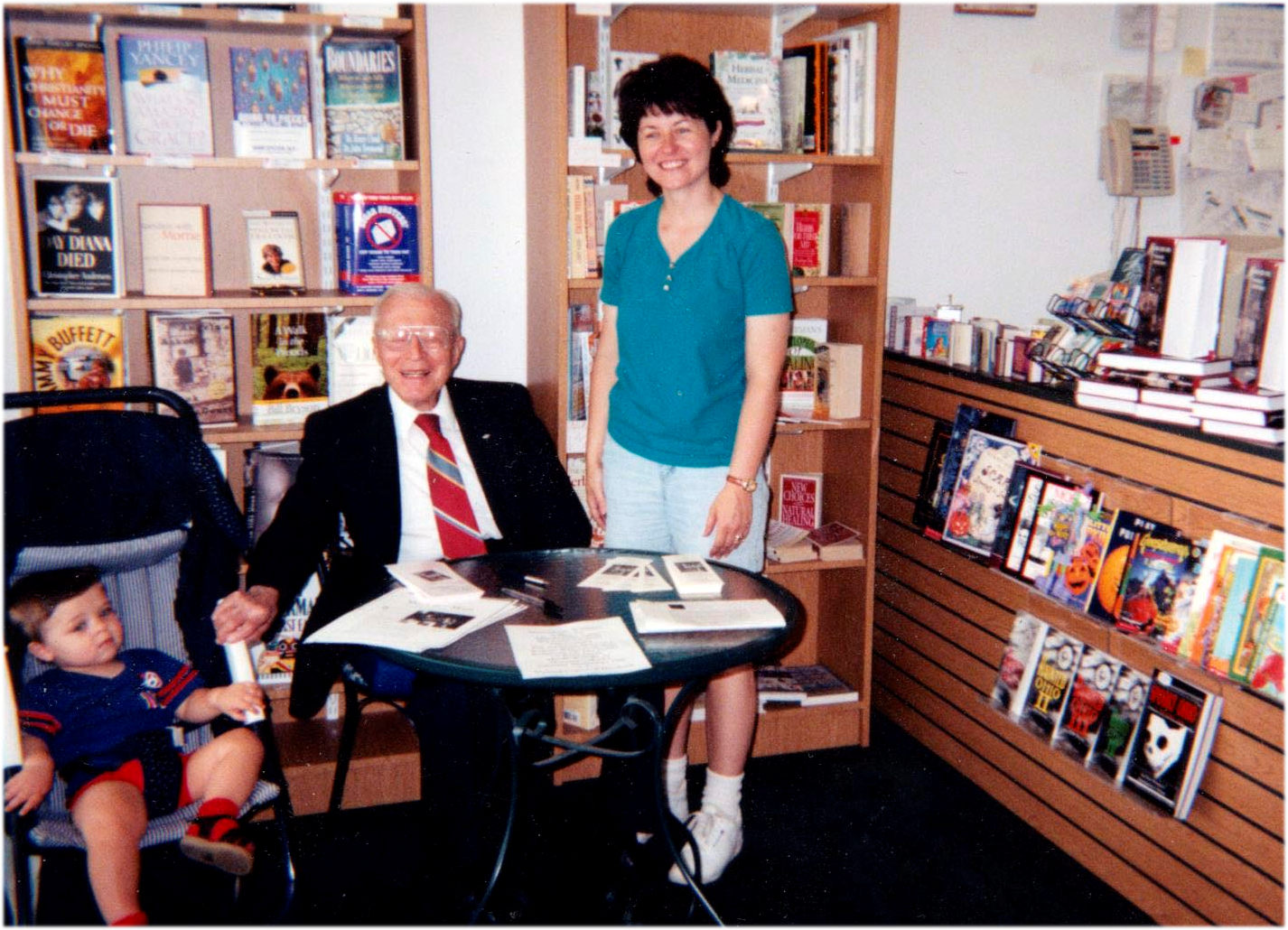

After 9 months of appearances and more to go, I tell myself that I am now ready for any developments, no matter how nerve wrenching or terror-laden; that I will not worry in advance. Maude (1883-1993): She Grew Up With the Country took me two years to write. Book signings and radio and TV interviews—first throughout Ohio, now in Florida—have introduced me to a whole new range of possible friends.  I travel from city to city, meet strangers, and tell people who are half my age how their parents and grandparents lived during the “primitive” early 1900s when their homes had neither electricity nor indoor plumbing. I am the sage! I am bemused by the attention I receive. Old friends shower me with a mixture of what I take to be admiration and envy. Strangers come up to me at book signings and marvel that I am able, in my 92nd year, to talk coherently and write intelligently.

Some wonder if I had a ghost writer. What I had was counsel and encouragement from a group of NYC professional writers to which my daughter belongs. They kept demanding more history, more biography, more family incidents, more anecdotes about the four active children and the fun-loving husband. So Maude grew from a small volume of limited interest to a century-end chronicle of 110 years’ worth of family values and the changes wrought by two world wars, the great depression, and inventions that helped place a man on the moon.

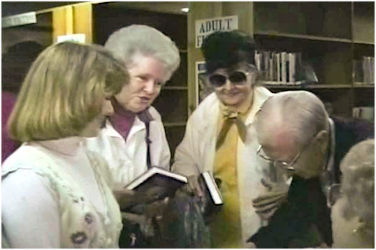

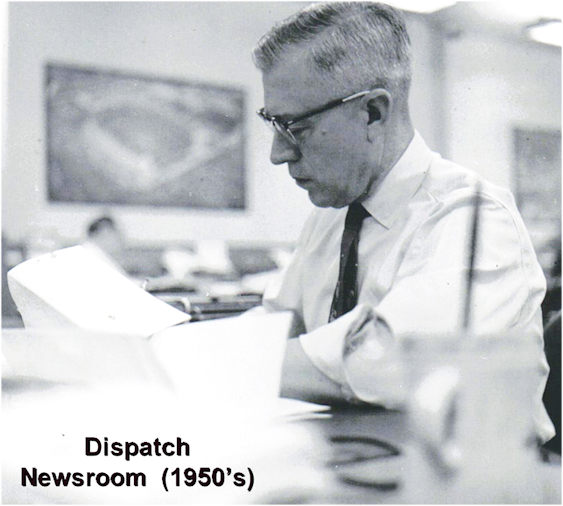

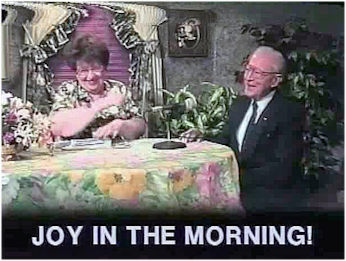

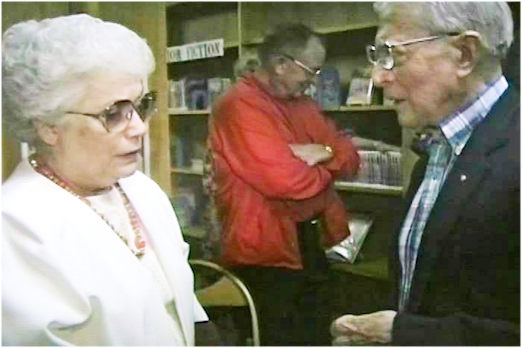

As a long-time newspaperman, I can write and carry on a conversation, but was at first intimi-dated by the thought of being inter-viewed on radio and television. I wondered how I would react to adversarial remarks from rude questioners. I began to lose my nervousness after radio host Allan Wolper assured me that most commentators want their guests to make a good impression. During a 30-minute phone interview for WBGO, Mr. Wolper inquired politely about the high spots of my 44-year news writing career, how I felt about journalism’s concern for political correctness, and why I wrote a book about my 110-year-old mother. Thanks to Mr. Wolper’s graciousness (and the fact I didn’t know I was being broadcast over one of New York City’s hottest stations), it was a snap. I thought every interview would be like that. I was rudely awakened at my next on-air appearance. The television interviewer was not prepared. He asked no pertinent questions and I was a novice, ignorant of how to jump in and save the cable program that was being broadcast to 130,000 families in the Cincinnati area. “This is not for me,” I told myself, then reversed my decision a few hours later when Gary Burbank gave me the opportunity to shine on his nationally syndicated Cincinnati radio show. The most memorable event of that day, however, was staged by Marie Verrastro, blind herself, as she transcribed a program for blind and handicapped people in the Greater Cincinnati area. Mrs. Verrastro had “read” the book—actually, it had been read to her by her husband—so she asked pertinent questions, then asked me to read a segment from the book so listeners could judge for themselves the quality of the story. She inspired me. Even if I have to face Howard Stern or Don Imus, I decided then, I will bear the humiliation with a smile. Dea Staley of WFXW Radio in St. Charles (IL) said she’d stayed up all night reading the book. She’d grown up with her grandmother on a farm. We talked for 40 minutes. I forgot I was on the air. She made me feel like a valued member of her family when she said, “I felt like I was in a corner of the room, watching everyone. I loved your mom, your sisters—but your dad was something else. I love a good bawdy story.”  Tanya Hutchins of Channel 6, Columbus, a charming interviewer, let me upstage her at will. She was so kind that I thought cockily, who’s next?--Oprah? Rosie? Regis and Kathy? The Today Show? But I lost my nerve again when I went to WNYC-AM to be a guest of Leonard Lopate, originator of New York City’s outstanding radio interview show. I knew he read every book of every author he interviewed. Would Maude stand up to the competition? When I blurted out I was a little hard of hearing, he outfitted me with a set of ear phones. I heard perfectly, I answered his questions, and breathed a sigh of relief when he told listeners he found it “fascinating to compare one person’s life with this country’s history.” Vick Mickunas of WYSO-FM, Yellow Springs (OH) telephoned me for a 30-minute interview. One of his questions was to talk about how the quality of life differed between when I was growing up and now. There was so much to say on that one, I stammered awhile, trying to answer without sounding like an old fogey. The show aired live before my book-signing at Dayton’s Books and Company. The nationally syndicated Paul Gonzalez Radio Show out of Tampa came the closest to sending me into a panic. After his associate “auditioned” me to see how loquacious I could be, Paul told me it was to be an hour-long telephone interview with breaks for the host’s comments about Maude and call-ins from interested listeners. I had never done call-ins before. I rehearsed my answers to anticipate his and listeners’ questions, and carefully arranged a half dozen information-laden sheets of paper on the table before me. I would flood the airways with rhetoric about this book, why it deserved to be written, and why I qualified to do it. Then Paul called. He had me rap the telephone against the table to clear up some fancied disturbance on the line—and my fears vanished. He was going to make it a fun experience. He asked me only four questions. I talked for less than ten minutes. He did the rest. He described Maude in more graphic and enticing terms than I ever could. He conversed with listeners who called from Kansas, Minnesota, Alabama, and Mississippi. He had me rap the phone on the table a few more times--just to make sure I was awake.  I had butterflies at my first bookstore signing, worried that no one would show up. It turned out to be standing room only. A television crew from Channel Four carried on-the-spot coverage. Borders Columbus sold 15 books—three to four times as many as I would sell at some later signings. At Marion’s Waldenbooks we sold out. I just happened to have a box with me in the car— which we made available to those who wanted signed copies. At 3:15, a woman dashed up breathlessly as we were about to leave. “Thank goodness, I caught you,” she said. “I just read the paper and saw you were here.” She introduced herself as the beautician from the Hardin County Home. She had done my mother’s hair for the last three years of her life. The largest signing I did was at the Book Store in Cape Coral. I signed 54 books because of a wonderful story in the Ft. Myers News-Press. At a Barnes & Noble in Toledo, a birthday cake was waiting for me. The staff had learned I was 91 that day. Among those who stopped by my signing table that night was an 83-year-old woman, facing hip replacement surgery the following day. She said she’d turned down a party to be given in her honor preferring to spend the evening talking about the “good old days” with the author. A Ft. Myers Waldenbooks had freshly baked cookies on my signing table—a splendid welcome both for customers and me.  My most disconcerting experience was when I drove 50 miles to a signing and found there were no books. Management had changed and none of the current staff knew I’d been scheduled that day. Many book signings have been inspirational. At Pt. Charlotte’s B. Dalton, an attractive woman chatted with me as she leafed through the book, bought a copy, then returned to confide that she was going to read it aloud to her blind daughter, who loved biographies and histories. A woman at Waldenbooks in St. Petersburg came with her 11-year-old daughter, an aspiring writer, to meet the author and buy a book. She found it difficult, her mother said, to write down what she really thought; it made her feel too vulnerable. I sympathized, knowing how hard it had been for me in writing Maude. |

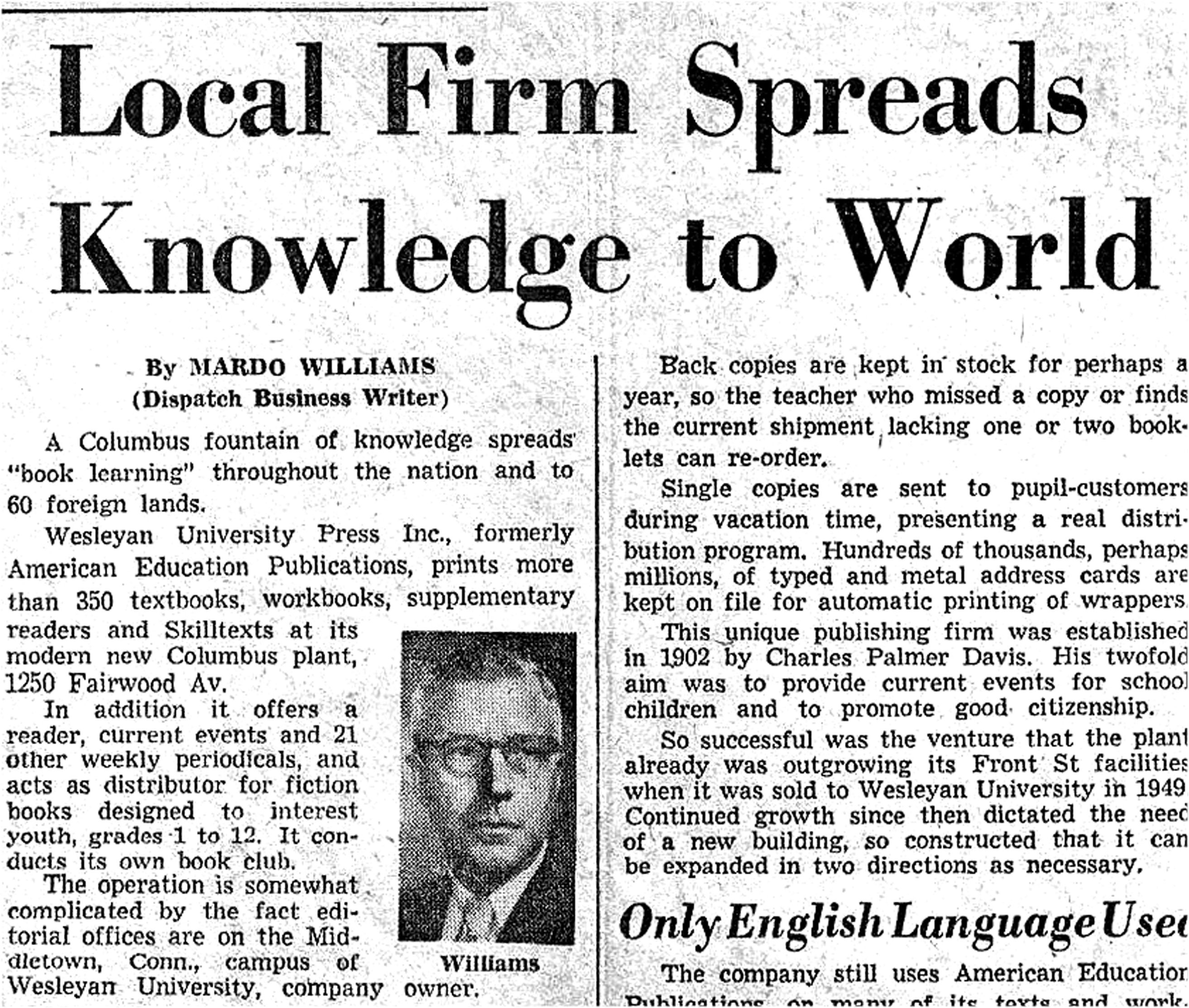

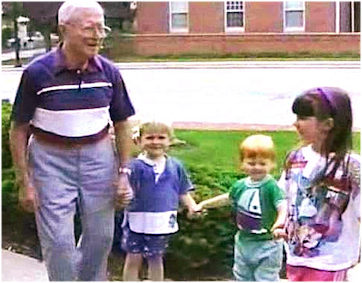

Many men seemed hesitant to buy this book about a woman. Some chatted several minutes about life as it was lived by their parents or grandparents. I would think I had a sale. Then they would leave with a wave and “good luck.” A few younger men purchased it as a gift for older relatives who had grown up under similar conditions of hard work, few opportunities, and homespun entertainment like charades, husking bees, and square dancing. Younger women have bought it for grandfathers or grandmothers; middle-aged ones, for mothers or fathers.  One woman in Dayton purchased seven copies for her grandchildren. “They need to learn about life as it once was lived--before computers and television.” Strangers come up to me at signings and report that they are related to me, either through my mother’s or father’s line. Even a few of my late wife’s relatives appear. I never knew my wife (an Ansley) and I were fourth cousins until I did the research for Maude and found out that my grandfather and her grandmother were second cousins in the Williams lineage. A cousin whom I have never met in El Cerrito, California wrote that she was griping to the beauty shop operator about her painful arthritis when she stopped abruptly and said: “I shouldn’t complain. My father’s first cousin lived to be 110. I can bear this little pain.” A second woman nearby spoke up: “That’s odd. I’m reading a book about a woman who was 110.” They said together, “Maude Williams.” The second woman added, “I went to school with Maude’s youngest daughter and my brother married her oldest daughter.” Two strangers who were almost-relatives then shared with each other the memories of growing up in two small villages of Ohio where they had electricity but no indoor plumbing. A 27-year-old English teacher, traveling in a crowded bus across South Korea to her new job at Chungnaman University, wrote that she had always wanted to know more about her grandmother’s life. Halfway through the book, she said, “I realized I was picturing my grandmother through it all. I will read it over and over again.”  Bonnie Comstock, a middle-aged Ohio farm woman, wrote that Maude “takes me home again. I haven’t been there in a long time.” Bonnie and I met two months after she mailed that letter. She’s a writer too and we send each other notes of encouragement.  My second career—the first was the 44 years I spent as a newspaper reporter—has re-introduced me to an associate of my childhood, eight or nine years younger than I. He has dementia, his daughter wrote. He has no short-term recall, but remembers the past in detail. He picks up Maude, she said, reads a few pages, smiles at the recollections and sets it aside.  Each year, there are fewer and fewer persons who can traipse back to the early 1900s with me. Marie Whetsel, age 93, one of eight in my graduating class, showed up with her daughter, Quo Vadis, at my Ridgemont Library signing. We hadn’t seen each other for 75 years. We reminisced about our favorite teacher at Ridgeway High, and Marie’s brother Harry who was good at sports. At Dayton’s Books and Company I met one of the few fans who is older than me (although only by 6 months)--Jackie Ballinger, 92 in February, whom I had met once in the early 1930s when I was a reporter in Kenton (OH). We became re-acquainted when she sent a card congratulating me on my 90th birthday. A year later, she convinced a friend to drive the 40 miles from Springfield to Dayton in a torrential rainstorm just to meet the author. Jackie is petite at four feet, 11 inches and 90 pounds. We have corresponded since. She is trying to convince me that I should retire to the Ohio Masonic Home, which has been her residence since 1991.  Erma Bowman is a comparatively new friend, although I had known her as my youngest sister’s best friend since 1916. She invited me to John Knox Village in Tampa, Florida, where she lives. We ignored the minor discrepancy in our ages to hug each other and talk of old times. We danced what may be our last waltz as she hummed “Moon River.” I told her, “I am getting too old for this.” She is not far behind—she will be 88 in June. “It’s time for you to retire,” she told me recently. “Why don’t you apply for an apartment here?” “Jackie wants me to move in where she lives--at the Ohio Masonic Home,” I said, knowing it would get a rise out of her. She and Jackie Ballinger have been friends since the 1920s. Now they are engaged in a pleasant rivalry—vying for the attention of a 91-year-old who thinks he is too young to contemplate any change in the tranquil course of his life. Recently, Erma’s surgeon told her that she shouldn’t be cremated because of all the steel rods in her shoulders and knees holding her body together. She wasn’t offended. “I got to laughing so hard I couldn’t stop. I guess death doesn’t frighten me anymore.” She will joke her way through the rest of her life, recalling choice memories all the way. When galleys of Maude were sent to the media, I was still shaky from a two-week hospitalization for pneumonia. I waited impatiently, fearfully for reviews. My spirits soared when Mike Harden of the Columbus Dispatch devoted a column of type to Maude terming it “an engaging and fascinating work about a courageous woman.” I read each succeeding review with assumed indifference, heart pounding. Each commentator seemed to take a different slant (some focused on history, others on the characters; some talked about family values, with Maude’s liveliness of mind and spirit at the center; others saw the book as a collection of tales about rural America). All were generous. I couldn’t believe they were talking about my book. Then I read a critic who, after conceding that Maude exemplified the strength and grace of our female forebears, added, “Her story, however, is plainly told without dash.” I dug through my collection of reviews, finding ones to re-read that approved of my newspaper writing style, terming it “clean, concise.” My life has changed drastically since 1992, when I first made notes for the book. My wife had just died.  My mother was in her 110th year. I wanted to ask her some questions before it was too late, and her answers became the basis for this book. I envisioned Maude as a book of about 50 pages—written for the family. When I finished and saw the large stack of papers on my computer desk, I couldn’t believe I had written all those words. With all the activity and new people I am meeting, I may never retire. As Lindsay Peterson wrote in her Prime Time column of the Tampa Tribune, it’s quite an occasion when someone I haven’t seen since 1920 walks up to me and says, “Remember me?” Sandra Mortham, Florida Secretary of State, read Lindsay’s article and felt obliged to drop a note. “Keep up the good work,” she wrote, which I interpreted as encouragement to all elderly persons to find new and interesting things to do as life winds down. Now if I can continue to do that, I will live another 10 years and finish my series of children’s vignettes, based on my adventures with my great-grandchildren [Great-Grandpa Fussy was published in 2000];  I will do a final draft of my book about the adventures of a fictional city family during a three-week farm vacation, and perhaps I’ll even write a romantic novel or two. [Mardo finished a first draft of One Last Dance before he died. It was completed by his daughters and published in 2005.]  I’ll need some activity to keep me from robbing a bank—or getting involved with a wealthy widow. Wish me luck! |

| ||||||||||

| Order · About The Author · About The Book · Excerpt · Critics Corner · Readers Speak · Contact Us · Home | ||||||||||

| ||||||||||

| ||||||||||

| ||||||||||

|

© 1999-2025 Calliope Press All rights reserved. For more information call 1-212-564-5068. |